Osteosarcoma and Allograft Bone Transplantation

Table of contents

Osteosarcoma is a primary aggressive bone cancer that often requires the removal of the affected bone segment. Historically, the only treatment for this disease was amputation, but advances in chemotherapy and reconstructive surgery have made limb-sparing procedures possible. A key component in limb preservation for osteosarcoma patients is reconstruction with allograft bone transplantation, where a donor bone (allograft) replaces the excised segment. This allograft can restore structural continuity and serve as a scaffold for the patient’s own bone to integrate. This article reviews the trajectory of allograft bone transplantation in osteosarcoma treatment, from early attempts to modern techniques, and examines different types of allografts (fresh versus frozen, irradiated, etc.), outcomes, and the latest innovations relevant for orthopedic and oncology surgeons.

Historical Milestones in the Use of Allograft Bone Transplantation

Bone transplantation has an astonishing history, with documented efforts dating back centuries. Below are some key milestones in the development of allograft bone transplantation worldwide:

1668 – First documented xenograft transplantation

A Dutch surgeon named Job van Meekeren is recognized as the first person to document a bone transplantation. He used a piece of a dog’s skull to repair a cranial defect in a soldier. This heterologous graft ultimately had to be removed due to religious objections, but it demonstrated the concept of bone transplantation.

He recorded many of his precise experiences and observations, including his expertise in hand surgery and techniques for draining abdominal fluids, in his influential book titled Heel- en Geneeskonstige Aenmerkingen (Medical-Surgical Observations). Published in 1668, this book serves as a valuable resource, reflecting the advanced surgical knowledge and skill in Amsterdam during that period.

1820 – First Autograft Transplantation

A German surgeon named Philipp von Walther performed the first successful autologous bone graft (using the patient’s own bone) and became a pioneer in bone transplantation during the pre-antiseptic era.

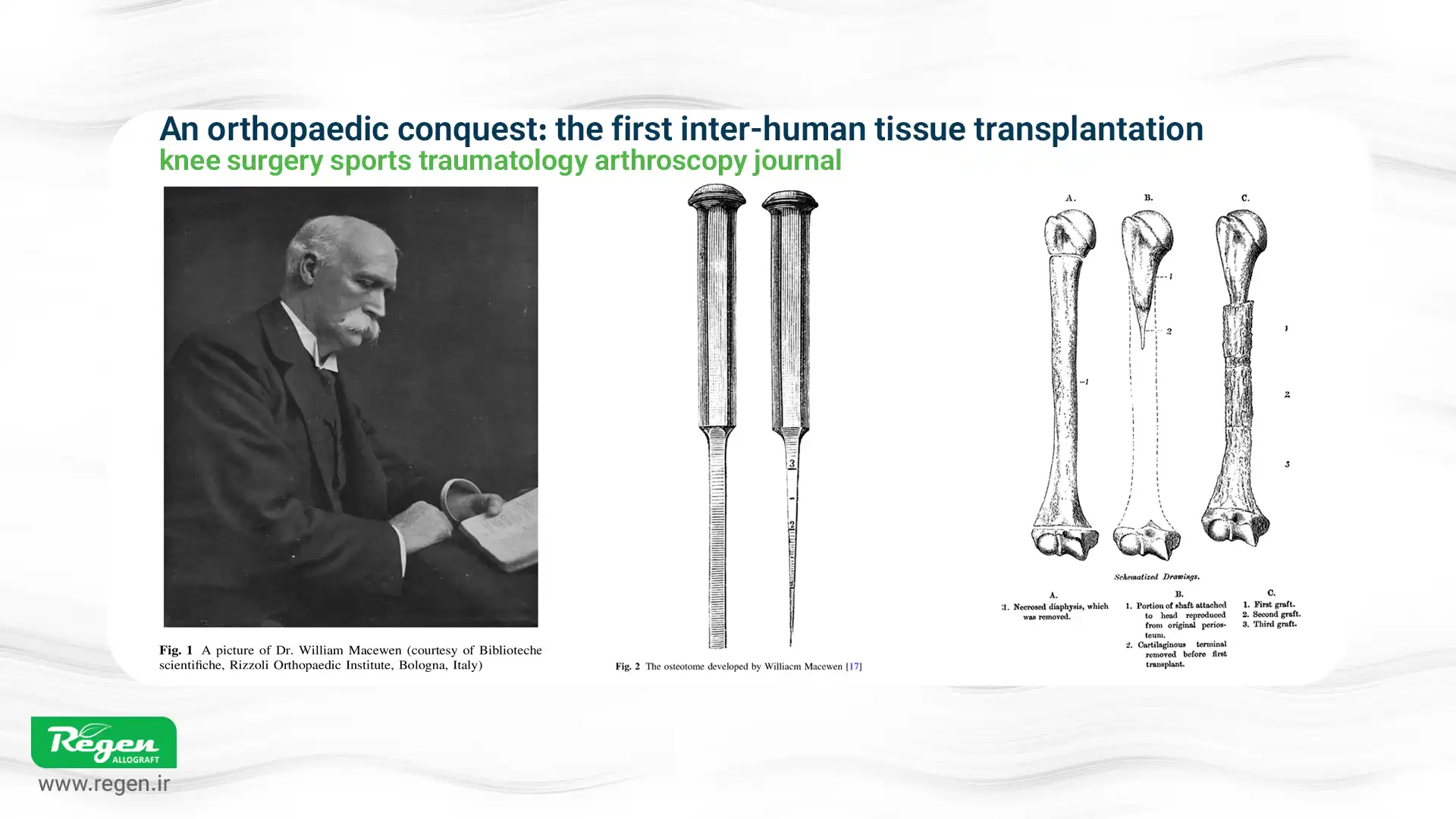

1879 – First Human Allograft Transplantation

A Scottish surgeon named William MacEwan performed the first human-to-human bone graft. He repaired a humeral defect in a 3-year-old boy using a donor bone from another patient. MacEwan’s report in 1881 demonstrated that the graft successfully integrated and the boy’s arm was saved; this marked a milestone in the early development of allograft surgery.

Early 1900s – Lexer’s Experiments

A German surgeon, Fritz Lexer, pushed the boundaries by experimenting with whole joint grafts and large bone segments from cadavers. In 1908, he reported the use of “free bone grafts,” and later, in 1925, he also attempted joint transplantation. Although many of these early large allografts failed due to infection or immune rejection (before the discovery of antibiotics and tissue typing), Lexer’s work laid the foundation for future reconstructive efforts.

1940s – Emergence of Bone Banks

During and after World War II, the concept of bone banks emerged to address the growing need for grafts. The U.S. Navy established the first National Naval Tissue Bank in Bethesda, and hospitals worldwide set up smaller bone banks. Donated bones from amputations or cadavers could be deeply frozen and stored. Early applications primarily involved small bone segments used to fill bone cysts, assist spinal fusions, or treat non-unions. This development ensured a reliable allograft tissue supply and paved the way for broader clinical applications.

1970s – Limb-Salvage for Tumors

The modern era of limb-salvage surgery began. Improvements in chemotherapy—which significantly increased survival in osteosarcoma patients—enabled surgeons to focus on reconstructing limbs after tumor resection instead of resorting to amputation. In 1973, Parish reported a series of 21 patients in whom long bone segments removed due to tumors were successfully replaced with massive cadaveric allografts, some including joint surfaces. Around the same time, pioneers such as Mankin, Enneking, and others in the USA, Canada, and Argentina began using massive osteoarticular allografts for bone tumors. These early series demonstrated that large allograft reconstructions could achieve acceptable function and preserve the limb, although complications were also observed.

1980s – Expansion and Alternatives

Many orthopedic oncology centers worldwide adopted allografts for reconstructing defects resulting from surgeries for osteosarcoma, Ewing sarcoma, and giant cell tumors. Surgeons also explored alternative limb-salvage techniques, such as modular endoprosthetic implants and megaprostheses. Allografts and endoprosthetic implants became the two main reconstruction options, each with its own advantages and limitations. Bone banking practices became more standardized (the American Association of Tissue Banks was established in 1976), and collaboration between surgeons and tissue banks increased to ensure a safe and reliable supply of grafts.

1980–2000 – Emphasis on Safety

With the increased use of allografts, adverse disease transmissions also occurred. Notably, several cases of HIV and hepatitis transmission via bone allografts in the 1980s raised alarms. The focus shifted toward safety: rigorous donor screening, improved sterile procurement, and final graft sterilization (such as gamma irradiation) became standard practice. During this period, the issue of allograft tissue availability was largely addressed through tissue banking, and safety became the foremost concern. Regulations and testing (e.g., for HIV, HBV, HCV) were implemented to protect both patients and tissue handlers.

2000s and Beyond – Enhancing Effectiveness

By the 21st century, with improved donor screening and sterilization, the risk of infection from allografts was drastically reduced. Attention has now shifted to the effectiveness and biology of allografts: how well they integrate, how their strength and healing can be enhanced, and how complications can be minimized. Research from 2000 to 2020 has explored adjuncts such as growth factors, stem cells, and novel processing methods to make allograft reconstruction more durable and predictable. These latest advancements will be discussed in the next section.

Types of Allograft Bone Transplants and Processing Methods

Not all allografts are prepared the same way. The methods of preservation and sterilization can significantly affect the biological and mechanical properties of the graft. Two main categories commonly referenced are fresh (or fresh-frozen) allografts versus frozen and irradiated allografts, each with its own rationale:

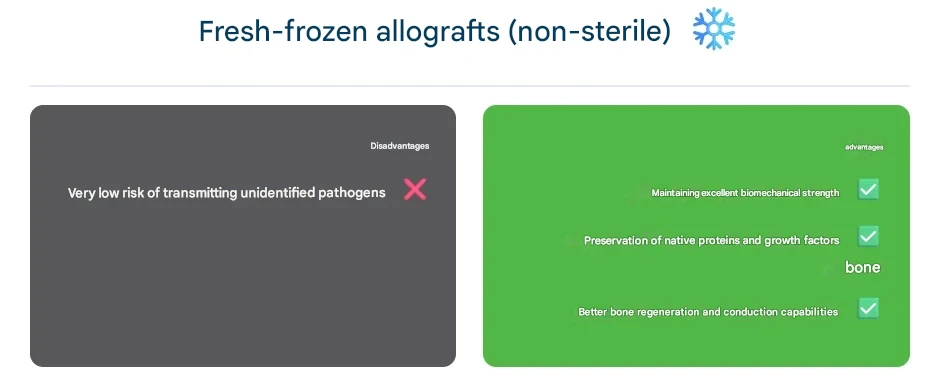

Fresh-Frozen Allografts (Non-Irradiated)

These grafts are typically harvested under sterile conditions, screened for pathogens, and stored frozen without additional terminal sterilization (usually at –80°C). In this context, “fresh” means the bone has not been chemically treated or heavily processed; it is preserved solely by freezing. Proponents argue that fresh-frozen grafts retain superior biomechanical strength and native cellular proteins, such as bone growth factors, compared to irradiated grafts. Studies have shown that fresh-frozen bone exhibits better osteoconductivity and remodeling because the collagen matrix and bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are less damaged. The drawback of this method is a very small risk of undetected pathogens, as safety relies on meticulous donor screening and processing rather than a dedicated inactivation step. In practice, many bone banks apply some form of sterilization to all grafts, but a graft labeled “fresh-frozen” generally indicates that it has not undergone high-dose irradiation or strong chemical sterilants.

Gamma-Irradiated Allografts

Gamma irradiation is the most common method for terminal sterilization of allograft bone. Grafts are exposed to gamma rays (typically from a Cobalt-60 source) at a standard dose of around 25 kGy, sufficient to eliminate bacteria, viruses, fungi, and even spores. This “cold sterilization” penetrates deeply into the tissue, providing an additional safety margin against disease transmission.

However, gamma rays also damage the graft’s delicate structure: collagen fibers are broken, and free radicals are generated, which can reduce the mechanical strength of the bone. Research shows that doses above approximately 25–30 kGy can significantly impair the biomechanical properties of cortical bone, making it weaker under fatigue and less stiff. High or repeated irradiation can also reduce osteoinductive proteins in the matrix, slowing graft integration.

Tissue banks have sought a balance by using the minimum effective dose (around 25 kGy) and sometimes irradiating under frozen or anaerobic conditions to reduce collagen damage. Nonetheless, a debate persists between safety and strength. Many surgeons prefer gamma-irradiated allografts for maximal infection protection, while others favor non-irradiated grafts for better biological performance.

Systematic reviews generally support fresh-frozen grafts for clinical outcomes, provided thorough donor screening is performed. For example, studies have concluded that fresh-frozen bone shows superior integration and biomechanical behavior, whereas irradiated bone, although safer regarding infection, is more prone to late complications such as nonunion or fracture.

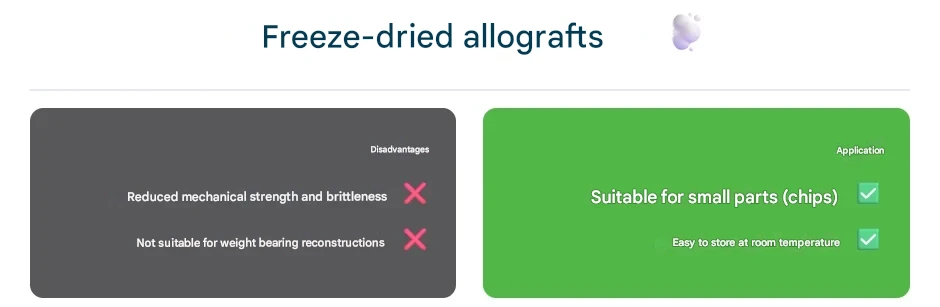

Freeze-Dried (Lyophilized) Allografts

In addition to fresh-frozen versus irradiated allografts, some grafts—particularly smaller segments, and not usually whole bones—are prepared as freeze-dried (lyophilized). Lyophilization removes moisture, allowing grafts to be stored at room temperature. However, freeze-drying can reduce both mechanical strength and osteoinductivity. Structural freeze-dried grafts are rarely used for weight-bearing bone reconstruction because they are brittle; this method is more common for morselized grafts or cortical chips used in spinal and dental procedures. For massive allografts in limb-salvage surgery, deep freezing (with or without irradiation) remains the standard.

Other Sterilization Methods

Historically, other techniques such as ethylene oxide gas and chemical sterilants were attempted but proved ineffective. For example, ethylene oxide left toxic residues (like ethylene chlorohydrin) that irritated tissues. Simply soaking in chemicals cannot reliably penetrate the center of large bones. Newer methods, such as supercritical carbon dioxide treatment or low-dose gamma irradiation combined with radioprotectants, are being explored to eliminate microbes while preserving graft quality. Electron beam (E-beam) irradiation is another option; it acts faster than gamma rays but has less tissue penetration, making it mainly suitable for thinner grafts. Currently, gamma irradiation at 25–35 kGy is an accepted compromise for sterilizing large bone allografts, with protocols designed to minimize its drawbacks.

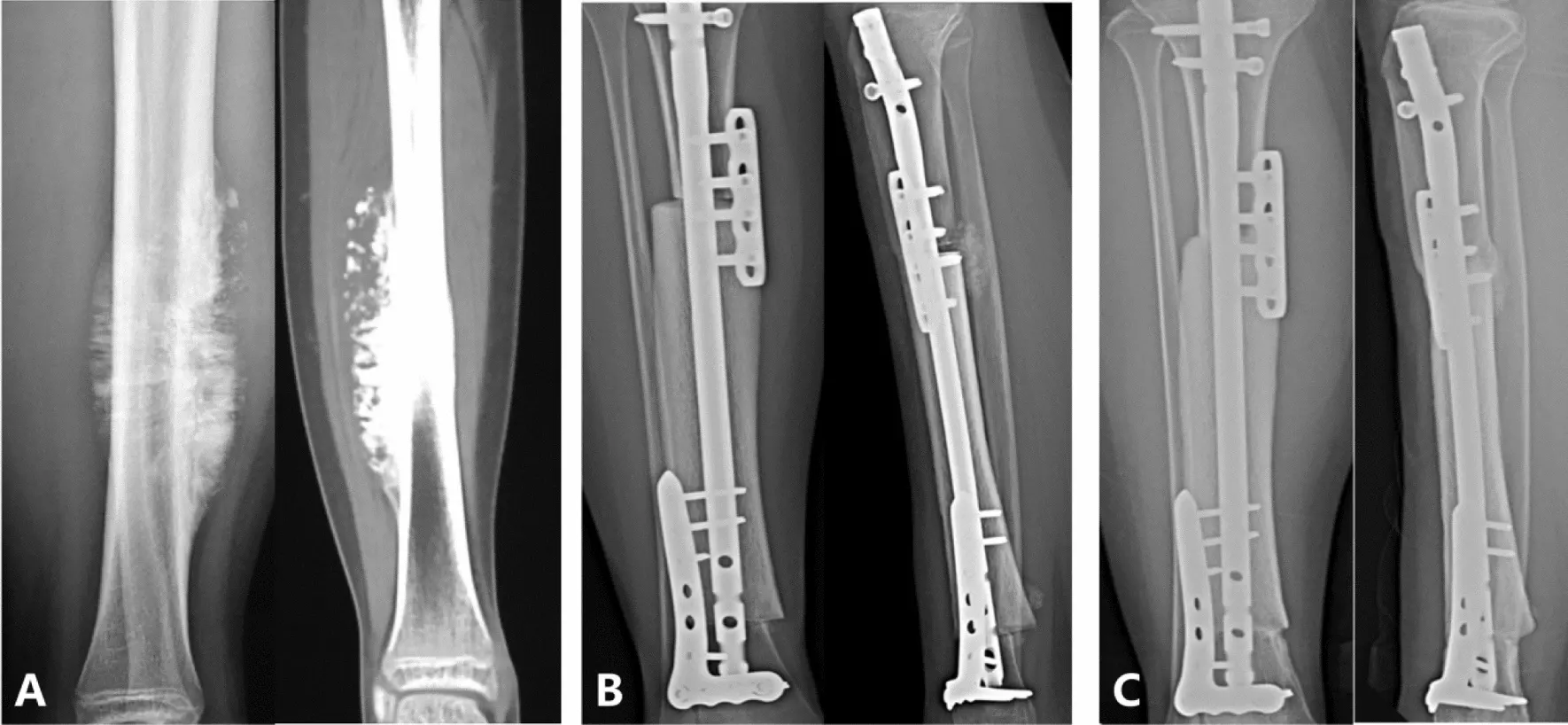

Allograft Bone Transplantation in Osteosarcoma Surgery

Using an allograft to reconstruct a large bone defect (for example, after tumor resection from the femur or tibia) is a complex but valuable technique. The surgeon shapes a cadaveric bone segment—usually obtained from a bone bank—to fit the excised portion. The allograft is stabilized in place with metal hardware (plates, screws, and intramedullary rods) and is sometimes combined with small autografts to enhance healing. Over time, the patient’s bone is expected to integrate with the allograft at the junctions, and the allograft gradually remodels through host revascularization. This approach contrasts with endoprosthetic replacement, where a metal implant substitutes for the bone and joint.

The primary advantage of an allograft in limb-salvage surgery

The main advantage of an allograft in osteosarcoma surgery is that it provides a biological reconstruction. Since it is real bone, once it integrates with the patient’s bone, it can potentially last for decades. Allografts serve as a scaffold for new bone formation and have sufficient strength to eventually support full weight-bearing. Unlike a metal implant, an allograft does not carry the traditional risks of wear or loosening.

Allografts are particularly useful for joint-preserving tumor resections: for example, if only part of a bone is removed, a properly shaped allograft can preserve native joint surfaces, offering better functional outcomes than replacing the entire joint. In the long term, a successfully incorporated allograft allows the patient to maintain a more “natural” anatomy. Additionally, allografts provide reconstructive surgeons with significant flexibility in shaping or trimming the graft to fit complex defects, such as in pelvic or scapular reconstructions where off-the-shelf prostheses may not be available.

Challenges and Complications of Using Massive Allografts

Massive allografts are associated with significant challenges. They initially lack blood supply, so integration is slow; the graft essentially acts as a dead scaffold that the body must gradually repopulate with blood vessels and bone cells. Complete remodeling of a large cortical allograft can take years. Consequently, the host-graft junctions often represent weak points. Nonunion—failure of the bone ends to fuse—occurs in a substantial number of cases, frequently requiring additional bone grafting or revision surgery. Infection is another major concern: a devitalized allograft has no immune defense, and if bacteria colonize it (via surgery or bloodstream), eradication can be difficult. Deep allograft infections may necessitate graft removal. Graft fracture is also a recognized complication; because the graft lacks living cells, it cannot repair microdamage like normal bone and may break, particularly if weakened by sterilization or poor healing at the ends.

A 24-year study of 870 massive allografts found that the most common serious complications were tumor recurrence, infection, fracture, and nonunion, which had the greatest negative impact on graft success. According to this study, the risk of deep infection was around 10% in the first year postoperatively, and graft fracture peaked at about 19% by the third year. If a graft survives the early high-risk period, it often becomes more durable; roughly 75% of successfully incorporated allografts remained functional even 20 years after surgery. This indicates that while the early period is risky, long-term outcomes can be very favorable for patients who pass the initial healing phase.

A specific concern for osteochondral allografts (grafts that include a joint surface, e.g., distal femur) is degenerative joint disease. The transplanted cartilage does not survive long; due to initial avascularity of the graft, the cartilage deteriorates. Many patients with osteochondral allografts eventually develop arthritis in the reconstructed joint. Mankin and colleagues reported that osteoarthritis became clinically significant about six years postoperatively, and approximately 16% of patients with knee or pelvic osteochondral reconstructions ultimately required conversion to a total joint prosthesis. Thus, when an allograft includes a joint, it often serves as a temporary solution for limb preservation and partial function, with the understanding that future joint replacement may be needed.

Comparison with Endoprostheses: Limb-salvage with an endoprosthetic implant provides immediate structural replacement and early mobility, without the risk of biological nonunion. However, implants have their own long-term issues: prosthetic joints may loosen or wear out, and particularly in younger patients, a prosthesis may require multiple revisions over a lifetime. Studies comparing allografts and endoprostheses show different failure patterns: allografts have higher biological complication rates (infection, nonunion, fracture), while endoprostheses exhibit higher mechanical failure rates over time (implant fracture, loosening). For example, a long-term study of knee reconstructions found structural failure rates of about 20% for allografts versus 10% for endoprostheses, but allografts reduced the need for repeated revision surgeries required for failed implants.

Short-term functional outcomes can be similar, but an allograft may feel more “natural” because tendons can reattach to bone, whereas an endoprosthesis provides more predictable early recovery with fewer initial complications. In practice, the choice often depends on patient age, tumor location, available grafts, and surgeon experience. Many centers selectively use both approaches.

Conclusion

From the first bone graft in the 17th century to today’s complex limb reconstructions, allograft bone transplantation has come a long way. In osteosarcoma treatment, allografts have enabled limb-salvage surgeries that would have been unimaginable in the era of routine amputations. We have seen how early surgeons like McEwen and Lexer laid the groundwork, how post-World War II bone banking made grafts widely available, and how the 1970s–80s established allografts as a viable option for massive defects. Along the way, the field learned hard lessons about safety, leading to rigorous donor screening and the adoption of gamma irradiation to nearly eliminate infection risk. Each decade brought improvements: refined surgical techniques, more precise graft processing, and adjunctive therapies to enhance healing.

Today, orthopedic oncologists have a diverse toolkit for managing large bone tumors: allografts, autograft recycling, endoprosthetic implants, or combinations thereof. Massive allograft reconstruction remains a cornerstone, particularly for patients seeking a biological solution that preserves native joints. Long-term studies indicate that when an allograft successfully incorporates, roughly three-quarters can last for decades, providing durable reconstruction and good function. However, complications—such as infection, nonunion, fracture, and joint degeneration—temper this success and remind us, as Mankin emphasized, that “research must continue to improve outcomes.”

Recent advances are precisely addressing these goals: combining growth factors and stem cells to “revitalize” grafts, using revascularized autografts or novel fixation techniques to strengthen them, and even exploring tissue-engineered bone and 3D-printed implants as potential future alternatives. It is an exciting era in musculoskeletal oncology, as science and engineering converge to make reconstructions safer and more effective.

In summary, the use of fresh-frozen and frozen allograft bone in osteosarcoma has evolved from an experimental idea into an established practice supported by global experience. From the simple first case in 1879 to pioneering research in 2025, allografts have continually adapted and improved. Surgeons and patients worldwide have benefited, turning once-lethal cancers into survivable conditions with functional limbs. Moving forward, ongoing innovation and rigorous clinical studies will ensure allograft reconstructions become even more reliable, helping patients not only survive osteosarcoma but thrive with pain-free, functional lives.

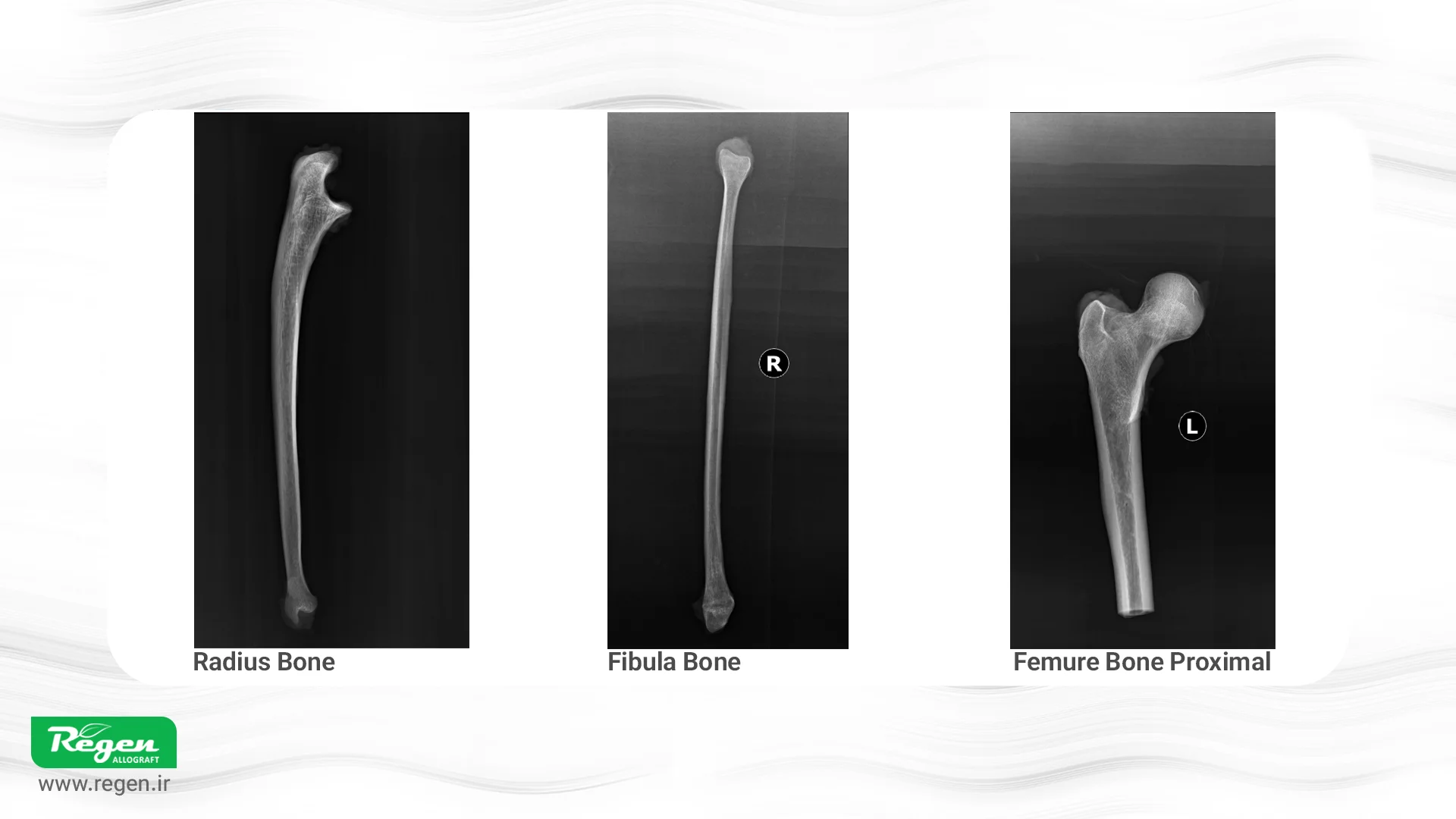

Regen Frozen Bone Products

One of the allograft products from Faraaradeh Bafte Iranian (Regen), marketed as Regen Allograft, provides frozen, gamma-irradiated bone for patients with osteosarcoma. Using standardized gamma irradiation, this product ensures high safety against viral and bacterial transmission while maintaining mechanical strength.

Processing Overview:

Sterile harvesting of bone tissue from qualified donors

Rigorous screening for infectious diseases

Deep freezing at –80°C

Final gamma irradiation for sterilization

Key Features of Regen Allograft:

High Safety: Gamma irradiation plus strict donor screening minimizes risk of disease transmission.

Mechanical Strength: Maintains sufficient load-bearing capacity for skeletal reconstruction.

Biocompatibility & Osteoconduction: Preserves collagen structure and bioactivity to support proper integration with host bone and serve as a scaffold for new bone formation.

Versatility in Complex Reconstructions: Suitable for large bone defects, including long bones and joint reconstructions after tumor resection, offering a biological alternative to prosthetic implants.

For more information or to place an order, please visit the official Regen Allograft page or contact us.

References

- An orthopaedic conquest: the first inter-human tissue transplantation, Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy (KSSTA), DOI: 10.1007/s00167-013-2669-7

- Bone allografts: past, present and future, Cell and Tissue Banking, DOI: 10.1023/A:1010158731885

- Fresh-frozen vs. irradiated allograft bone in orthopaedic reconstructive surgery, Injury, DOI: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.01.116

- Radiation sterilization of tissue allografts: A review, World Journal of Radiology (WJR, World J Radiol), DOI: 10.4329/wjr.v8.i4.355]

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 5 / 5. Vote count: 3

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Relevant Posts

Free consultation

Do you need counseling?

The professional and specialized team at Allograft is ready to assist you