Diagnosis of periodontal bone defects: The key to successful allograft transplantation

Table of contents

Why is Alveolar Bone Architecture Critical?

Periodontal disease is an inflammatory and multifactorial process, the most prominent consequence of which is the loss of alveolar bone support. The true challenge emerges at the time of surgical exposure, when the three-dimensional (3D) configuration and actual morphology of osseous defects become evident. This precise morphology is the key determinant for selecting the appropriate regenerative technique and biomaterials.

Core Issue: The loss of vital support

Periodontal disease is an inflammatory process whose most significant outcome is the destruction of alveolar bone. This bone forms the foundation of dental stability, and its loss poses major therapeutic challenges.

In fact, any misjudgment in estimating the number of walls, depth, or width of a defect may lead to complete treatment failure. Profound knowledge and accurate classification of periodontal osseous defects (PODs) form the cornerstone for designing successful reparative or regenerative strategies. In today’s era, where advanced regenerative techniques and modern grafting materials such as allogeneic bone grafts (allografts) play a central role, a clear understanding of defect topography directly influences graft particle size selection, material volume, and overall treatment outcome.

The aim of this article is to review the classification of periodontal osseous defects and emphasize their undeniable role in clinical decision-making for bone regenerative interventions, with a focus on the optimal use of allografts in surgical practice.

The Complexity of Alveolar Bone Loss

Alveolar bone, derived from ectomesenchymal origin, serves as the supporting column of teeth, and its reduction acts as the main driver of periodontal attachment loss. The patterns of destruction may be horizontal, vertical, or combined. Clinical evidence demonstrates that vertical defects occur more frequently in posterior teeth—particularly in the mandible—and two-wall craters are among the most common patterns. Such crater-like lesions often provide a contained environment with high regenerative potential for allografts, provided that the defect depth is adequate.

Accurate surgical exploration to understand the true morphology of the defect is the prerequisite for proper grafting technique selection and predictable regenerative success.

A Practical and Modified Classification of PODs

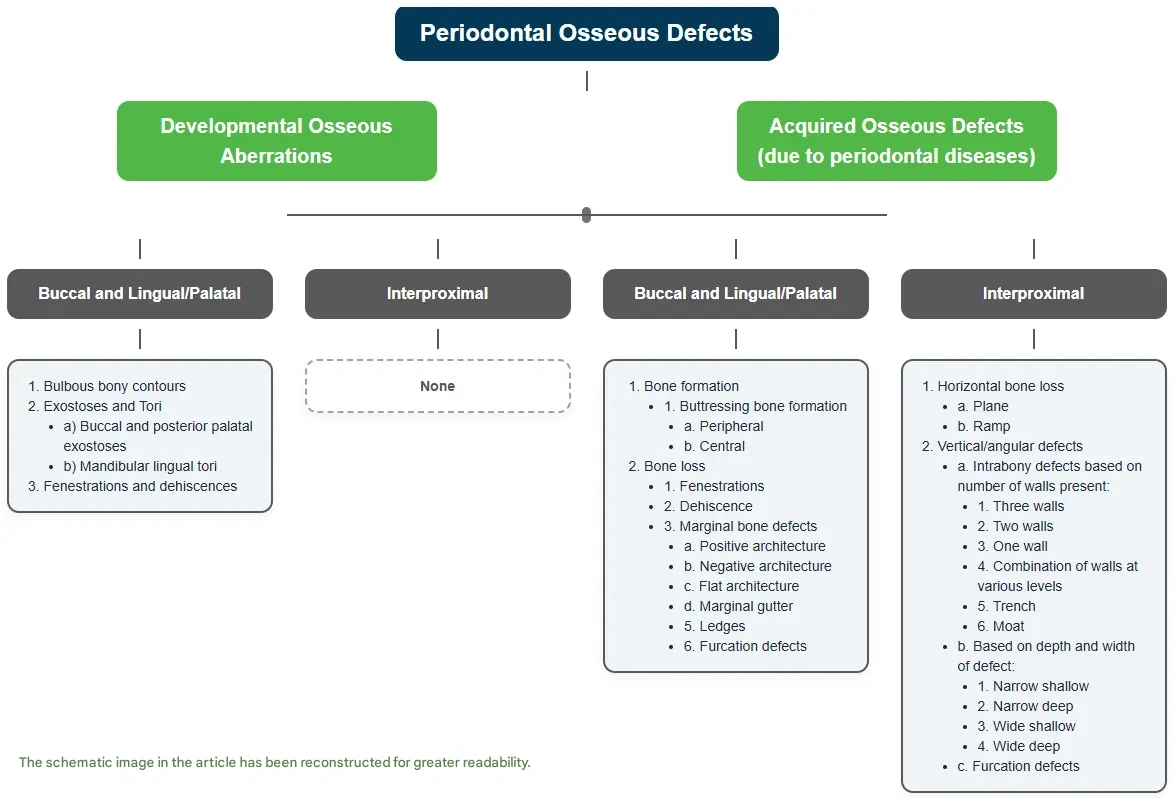

Classical morphology-based classifications (e.g., Goldman–Cohen or Pritchard) are not always sufficient for intraoperative decision-making. A modified classification proposed by Vandana and Bharath divides periodontal osseous defects into two main categories, offering comprehensive guidance for clinicians:

1. Developmental Osseous Aberrations

These result from anatomic variations, genetic factors, or adaptation to abnormal function. Although not inherently pathological, they influence surgical access, flap design, and final architecture. They should be evaluated—and often corrected—prior to regenerative procedures:

Bulbous contours: May complicate probing and flap adaptation, affecting esthetic outcomes.

Exostoses / Tori: Selective removal is advised to improve surgical access and maintain biologic width.

Fenestrations / Dehiscences: Accurate diagnosis is essential for planning root coverage and esthetic procedures; combining allografts with soft tissue grafting can enhance thickness and support.

2. Acquired Osseous Defects

These are consequences of chronic periodontal inflammation and are directly related to long-term prognosis:

Buccal / Lingual / Palatal defects: Include buttressing bone formation and variations in positive, negative, or flat architecture. Correction of reverse architecture via osteoplasty is often required to establish favorable conditions for effective graft integration.

Interproximal defects: Represent the core of regenerative decision-making, particularly in vertical or angular defects.

Diagnosis of periodontal bone defects: The key to successful allograft transplantation

Predictability of Regeneration

Three-Wall Defects

These defects, bordered by one tooth surface and three osseous walls, represent the ideal morphology for periodontal regeneration. The presence of three bony walls creates a natural container, providing maximum space confinement and cellular support for the placement of an allogeneic bone graft. Such conditions offer the best prognosis for successful graft incorporation and its function as a scaffold for new bone formation (osteoconduction). The stability of the blood clot within this protected environment serves as the primary key to successful regeneration.

Two-Wall Defects

These include osseous craters, defined by two tooth surfaces and two bony walls (buccal and lingual). They are the most prevalent type of defect in the posterior mandible. Regeneration of these lesions requires more precise techniques; commonly, allografts are combined with guided tissue regeneration (GTR) protocols, using barrier membranes to compensate for the missing third and fourth walls and to prevent epithelial cell migration into the defect.

One-Wall Defects (Hemiseptum)

These more complex lesions carry a poorer regenerative prognosis and represent a major challenge for the retention and stability of allografts. Due to the lack of sufficient lateral support, the risk of graft resorption and collapse is considerably high. Regeneration in such cases requires combined and staged approaches, since the number of bony walls typically decreases from apical to coronal. Layer-by-layer management based on defect depth and containment at each level is essential.

Defect angle and depth are also critical: deep, narrow-angled (V-shaped) lesions provide a more favorable site for graft stabilization and thus demonstrate a better prognosis.

The predictability of regeneration is directly proportional to the number of remaining bony walls.

Furcation Defects: Strategic Use of Allografts in Multi-Rooted Teeth

In multi-rooted teeth, furcation involvement refers to disease penetration into the bifurcation or trifurcation area. Based on Glickman’s classification (Classes I–IV), the extent of destruction is graded as follows:

Class I & II: Represent partial or limited horizontal bone loss. In Class II defects—particularly those with a cul-de-sac morphology—bone regeneration using allografts is highly effective. The crater-like configuration offers a contained environment where graft materials can be stabilized, promoting vertical bone formation and preventing progression to more advanced stages. The adjunctive use of biologics (e.g., enamel matrix derivatives) can further enhance regenerative outcomes.

Class III & IV: Indicate complete osseous destruction with through-and-through involvement. Although full regeneration is challenging, allografts can still be utilized to fill defect volume and prepare the site for techniques such as tunneling or root resection, thereby prolonging tooth survival.

Why Allografts Are the Logical Choice

Bone allografts represent the cornerstone of modern periodontal regeneration due to their biocompatibility, availability, avoidance of donor-site morbidity, and reliable osteoconductive properties. Their greatest effectiveness is seen in three-wall defects and deep craters. Success is contingent upon three principles:

Appropriate selection of graft type and particle size according to defect morphology.

Space maintenance with suitable tools (membranes, meshes, pins) and secure fixation.

Soft tissue management to prevent exposure and ensure clot stability.

Suggested Clinical Decision-Making Algorithm

Surgical exposure and 3D assessment: Record the number of walls, depth, width, and angle.

Evaluate regenerative potential: Does the lesion possess biological capacity for regeneration?

Select graft material/technique:

Allograft alone for well-contained defects.

Allograft + GTR with membrane for insufficient walls.

Allograft + mesh/pin for one-wall defects.

Soft tissue and risk management: Flap design, tension-free closure, and strict aseptic protocol to minimize risk of exposure.

Accurate diagnosis of defect morphology is possible only through direct surgical visualization and probing; radiographs serve merely as an initial guide. Translating this diagnosis into an evidence-based, graft-centered surgical plan enhances prognosis, optimizes material efficiency, and aligns clinical practice with contemporary standards.

Cortical Plate and Cortical Disk Products

In response to the challenges posed by non-contained defects, Iranian Tissue Products Company, under the brand name Regen Allograft, introduced its Cortical Plates—an innovative solution specifically designed for space maintenance, minimizing soft-tissue collapse, and enhancing allograft stability in complex defects. Technical specifications, user guidelines, and preliminary laboratory/clinical data will be released in the upcoming report.

Following the success of this product and the positive reception from specialists who have already applied it in clinical practice, a new material—Cortical Disk—has recently been launched. For further details and clinical insights, you may refer to the dedicated product page.

Cortical Disk and Cortical Plate under the brand name Regen Allograft for the reconstruction of non-contained bone defects

References

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 5 / 5. Vote count: 2

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

Relevant Posts

Free consultation

Do you need counseling?

The professional and specialized team at Allograft is ready to assist you